Homemade: Finnish Rye, Feed Sack Fashion, and Other Simple Ingredients from My Life in Food by Beatrice Ojakangas. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016. 216 pp., 40 b&w photos.

Homemade: Finnish Rye, Feed Sack Fashion, and Other Simple Ingredients from My Life in Food by Beatrice Ojakangas. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016. 216 pp., 40 b&w photos.

I thank University of Minnesota Press for providing an advance copy of this book, which should be of special interest to Northern Lights readers.

Finnish-American chef and prolific cookbook author Beatrice Ojakangas has gifted her loyal readers and new fans with a most beautiful and heartfelt memoir of her life in food–a well-told tale of family origins, inborn talent, opportunities seized, and hard work–flavored throughout by her own irresistible spirit. I count myself among the loyal readers, since I own three of her cookbooks–The Finnish Cookbook, Scandinavian Cooking, and Scandinavian Feasts–the latter two also published by University of Minnesota Press.

In Homemade, I learned more about how she came to write The Finnish Cookbook, her first book, after a Fulbright grant to her husband Dick allowed the young family (she and Dick had two children by then) to spend a year in Finland, a year which Beatrice put to good use listening to people and collecting recipes. From that book, I already knew Beatrice Ojakangas as an engaging writer on Finnish culture as well as a food expert.

But wait! I am getting ahead of myself and ahead of Beatrice, who begins Homemade at the beginning, with her family. Part I is devoted to the story of her grandparents, her parents, and her growing-up years on a northern Minnesota farm as the oldest of ten children. As she writes, “I’m 100 percent Finnish” and “I’m also 100 percent Minnesotan.” All four of her grandparents immigrated from Finland to Minnesota. She begins her chapter on her paternal grandparents with the poignant sentence, “I often wonder who I would be if my father’s mother had married the man she loved.” As a young woman, her grandmother Susanna (“Sanna,” or “Mummu” to her grandkids), born in Lapua, Finland in 1872, had fallen in love with a young Lutheran pastor who went on ahead to live in America, promising to send her a boat ticket to join him later, when they would be married. After months went by without hearing from him, Sanna regretfully accepted a proposal and ticket from another young man who had gone to make a new life in Minnesota. Just as she was packing to leave, another ticket arrived in the mail, one from her true love. But she kept her promise to the man she had accepted and left Finland with the pain of lost love in her heart.

My brief telling only gives a glimpse of the moving way Beatrice recounts this story, along with the sequel many years later, when Sanna met her first love again. Beatrice writes about her grandfather with respect for the hard but good life he provided for his family, the farming and logging work he did, with Sanna working hard on the farm too. The family that was, rather than the family that might have been, became the one that gave birth to her father Isä, who shared with his mother Sanna a love of roses and gardening. This chapter finishes out with a delectable recipe for Finnish Cardamon Coffee Bread, or Pulla; it is also found in Finland as nisu (a Swedish name for it) or vehnäleipä (wheat bread). Leftover bread (if there is any!) can be sliced and toasted to make korppu, the Finnish equivalent of biscotti, for dunking in coffee or hot cocoa.

Her mother’s father, Joel, the only one of five brothers to survive a terrible famine in Finland, also came to America and eventually settled in Minnesota. He was the one who gave his granddaughter the nickname “Peachie” or “Peaches” because her given name, Beatrice, unfamiliar to Finnish ears, sounded like “peetsi” (peach). She writes about this so affectionately, it is clear that she cherishes this lifelong nickname and its association with her good-natured grandfather. He was also courageous, saving his two little daughters from a fire. Little Esther, who bore swirling scars to remember this ordeal by, would grow up to be Beatrice’s mother. Esther’s mother Ruusu died in 1918 (the year of a flu epidemic) and Joel, while still grieving, needed help with his farm and his children; he sent to Finland for a mail-order bride, Helena, who happened to be a professionally trained chef who had worked in Helsinki. Her special cooking skills were a sign of things to come in a later generation. Beatrice includes a recipe she pieced together, with a little trial and error, for Grandmother Helena’s sugar cookies. Although Helena didn’t let little Esther in the kitchen, she must have picked up a lot on her own. She was determined to teach her own children, starting with Beatrice, to cook before they could read–something the author is duly proud of, both her early cooking skills and her brave and generous mother who passed them along.

I hope these stories give a peek at the delightful family that Beatrice lets us in on. My favorite chapter is probably “There Were Ten of Us” in which we get a brief but fascinating portrait (including some charming family photos) of each of her nine siblings, four boys and five girls. One can’t be the oldest of such a crew without witnessing some major heartache and some triumphs too. She shares these tenderly and with an appealing pride in her siblings. The chapter called “Being Finnish” speaks honestly about the relations among different groups coexisting in an immigrant-rich state like Minnesota, and it offers a brilliant description of the very Finnish custom of sauna bathing every Saturday, to get scrubbed shiny clean for Sunday Lutheran services. This Saturday night ritual finished joyfully with a meal of delicious Lattyja (thin Finnish pancakes).

There is much more to tell from Beatrice’s early years, but I’ll let readers discover the stories and recipes for themselves. I’ll just mention that the “Feed Sack Fashion” in the book’s subtitle (and its own chapter) proves that her talents extended to sewing as well; she made clothes for her sisters and brothers from feed sack cloth in various prints available for free during the 1940s. The book includes a photo of her with her sisters, all wearing lovely matching dresses she designed and sewed herself; it was published in Seventeen magazine in a story on small town life.

In Part II, Beatrice has embarked on her career as a home economist. As a 4-H girl, she had already won State Fair prizes for her Cheese Soufflé and her Finnish Rye Bread (clippings, with photos of the young cook are included!). While the cooking classes at the University of Minnesota’s Home Ec department were “nothing new” to this experienced home cook, she loved the chemistry and physics courses. One summer job at a private home gave her an on-the-spot apprenticeship in cooking “gourmet food” in quantity for large parties. In 1956 Beatrice Luoma married Dick Ojakangas, a geologist. While they were stationed in England for his ROTC, she learned about the Pillsbury Bake-Off. She won the Second Grand Prize for her Cheesy Picnic Bread (Chunk o’ Cheese Bread), and she hadn’t even had enough ingredients on hand to test out the variation she submitted!

I have already told you that Beatrice and Dick spent a year in Finland. When they returned to the States, they lived in Stanford, California and Beatrice landed her “dream job,” working at Sunset magazine. Working her way up from typing recipes to pitching ideas at planning meetings, she eventually began writing stories. She also did recipe testing for others in the Sunset test kitchens. Eventually, she presented her project for a cookbook of Finnish recipes to the publishers, and although they couldn’t publish it, they directed her to Crown Publishers: The Finnish Cookbook was born, and so was a new cookbook author. Since then she has written another 28 books about Scandinavian food and many kinds of food, for large crowds or just for two. Returning to Minnesota, and raising her own family, she still had many adventures to come, inventing what became the Jeno’s Pizza Roll for Chun King and appearing on television with both Julia Child and Martha Stewart.

Both the personal stories and career milestones are narrated in short, witty, and highly companionable chapters, punctuated by food-related incidents and capped by inviting and accessible recipes. As an excerpt from the book, I present the chapter “No Recipe Needed” (pp. 56-57), which includes the recipe for Mummy’s “Juicy” Cinnamon Rolls. Beatrice’s story of how her mother made these in quantity on the farm, working from memory and instinct (“no recipe needed”), and baking them in her wood-burning stove, pairs so well with the carefully documented recipe for home cooks today. Together, the story and the recipe should give a beautiful sense of the riches this book has to offer.

Excerpt*

No Recipe Needed

There were always cinnamon rolls in our farm kitchen for snacks or to go with coffee. Mummy felt that the yeast-raised, slightly sweet rolls were much healthier than sugar- and fat-loaded cookies. She baked a huge batch of coffee-glazed cinnamon rolls at least once or sometimes two or three times a week, depending on what was going on. If we had many hired hands around, as in the spring for planting, or in the fall when Isä had lots of outdoor work to get done, that’s when we needed more kahvileipä [coffee bread].

When I searched her files for the recipe, I found only recipes from family and friends, but not Mummy’s cinnamon rolls. Reflecting on this, I remember her saying—“I just make them.” She didn’t need a recipe.

Here’s how it went. She would take the big tin bread pan down and smash a cake of yeast with a little sugar until the yeast made a smooth, soft paste. To that she would add three or four quarts of lukewarm milk and a little more sugar. Then she’d add the salt, some fresh eggs, sometimes six, sometimes eight (eggs make the dough nice and tender). Next, she’d start adding flour, slowly at first so that she could beat the batter until it was nice and smooth. She’d taste the batter and add enough sugar to make it taste good. Not too much. Then more flour, keeping the dough smooth. Before kneading the dough, she thought it was a good idea to let it “rest” for fifteen minutes or even half an hour until the yeast had a chance to permeate the batter and it became puffy. Then she would sprinkle more flour over the top and begin turning the dough over on itself (she did this by hand in her big bread pan). As she turned the dough over on itself, she would sprinkle more flour over and punch it into the center of the mixture. When the dough had enough flour added, it would no longer stick to her fingers. Then, she’d check to see there was no more “loose” flour and turn the dough over so the top of the batch was smooth. She would cover the dough with a muslin towel and then put on the pan’s metal cover and put it into a warm place to rise. This would take an hour or so.

Once the bulging pan of dough had risen, she’d cut off about an eighth of it and slap it down onto a lightly floured countertop and roll it out to about ½-inch thickness. Next, she’d spread the dough with soft butter and sprinkle it generously with cinnamon sugar and roll it up. With a knife (or sometimes with a string) she would cut the roll into 1-inch slices and place them on a greased cookie sheet. This she repeated until all eight portions of the dough were shaped into rolls.

There were about a dozen cookie sheets of dish-towel-covered rising rolls on every surface in the kitchen. On the woodstove there would be a syrup of coffee and sugar (about ¼ cup sugar to each cup of coffee), boiling. The rolls were baked about 10 minutes or so in a 375°F wood-fired oven. Then, when she took the pale-golden rolls out, Mummy would slather them with the coffee syrup to make them juicy. The sixteen dozen rolls that her recipe made sometimes lasted two days!

Here’s a smaller rendition of the juicy cinnamon rolls adapted to my favorite “refrigerator dough method”:

***

Mummy’s “Juicy” Cinnamon Rolls

2 packages active dry yeast

1 cup warm water

½ cup melted butter

½ cup sugar

½ cup nonfat dry milk

2 eggs

1 teaspoon salt

About 4 cups all-purpose flour

Filling

½ cup soft butter

½ cup brown sugar

1 tablespoon cinnamon

Coffee glaze

1 cup powdered sugar

Hot strong coffee

In a large bowl, combine the yeast and warm water. Stir. Let stand about 5 minutes or until the yeast foams. Stir in the butter, sugar, dry milk, eggs, and salt. Beat in flour, 1 cup at a time, until the dough is too stiff to mix; you may reach that stage before you have added all the flour. Cover and refrigerate 2 hours or up to 4 days.

On a lightly floured board, cut the dough into two parts. Roll one part at a time to make a rectangle 12 inches square. Spread with ¼ cup soft butter. Mix the sugar and cinnamon and sprinkle with half the brown sugar mixture over the dough. Roll up into a firm, log-shaped roll. Cut diagonally to make about 1-inch slices. Place rolls on a greased baking sheet and let rise for 30 minutes or until golden.

Preheat the oven to 350°F. Bake the rolls for 10 to 15 minutes or until golden. Mix the powdered sugar with enough hot coffee to make a thin glaze. Brush baked rolls with the glaze.

Makes 24 large cinnamon rolls

*Reprinted with permission from the University of Minnesota Press from Homemade: Finnish Rye, Feed Sack Fashion, and Other Simple Ingredients from My Life in Food by Beatrice Ojakangas. Copyright 2016 by Beatrice Ojakangas. www.upress.umn.edu

From the Publisher

A celebrated cook’s recipes and reflections on growing up in a big Finnish family in northern Minnesota.

Beatrice Ojakangas, the oldest of ten children, came by it naturally—the cooking but also the pluck and perseverance that she’s served up with her renowned Scandinavian dishes over the years. In the wake of the Moose Lake fires and famine of 1918, Ojakangas tells us in this delightful memoir-cum-cookbook, her grandfather sent for a Finnish mail-order bride—and got one who’d trained as a chef.

Ojakangas’s stories, are, unsurprisingly, steeped in food lore: tales of cardamom and rye, baking salt cake at the age of five on a wood-burning stove, growing up on venison, making egg rolls for Chun King, and sending off a Pillsbury Bake Off–winning recipe without ever making it. And from here, how those early roots flourished through hard work and dedication to a successful (but never easy) career in food writing and a much wider world, from working for pizza roll king Jeno Paulucci to researching food traditions in Finland and appearing with Julia Child and Martha Stewart—all without ever leaving behind the lessons learned on the farm. As she says, “first you have to start with good ingredients and a good idea.”

Chock-full of recipes, anecdotes, and a kind humor that bring to vivid life the Finnish culture of northern Minnesota as well as the wider culinary world, Homemade delivers the savory and the sweet in equal measures and casts a warm light on a rich slice of the country’s cooking heritage.

About the Author

Beatrice Ojakangas grew up on a small farm in Minnesota and graduated from the University of Minnesota–Duluth. Childhood 4-H, college Home Ec, and work as a hospital dietary assistant, food editor, teacher, homemaker, and mother influenced her cooking career and her food writing for such publications as Gourmet, Bon Appétit, Woman’s Day, Family Circle, Better Homes and Gardens, Midwest Living, Cooking Light, and numerous newspapers. Ojakangas is the author of 29 cookbooks and was inducted in 2005 to the James Beard Cookbook Hall of Fame. She received an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters from the University of Minnesota in 2007.

The Axe (The Master of Hestviken, Vol. 1) by Sigrid Undset. Vintage, 1994.

The Axe (The Master of Hestviken, Vol. 1) by Sigrid Undset. Vintage, 1994.

Homemade: Finnish Rye, Feed Sack Fashion, and Other Simple Ingredients from My Life in Food

Homemade: Finnish Rye, Feed Sack Fashion, and Other Simple Ingredients from My Life in Food

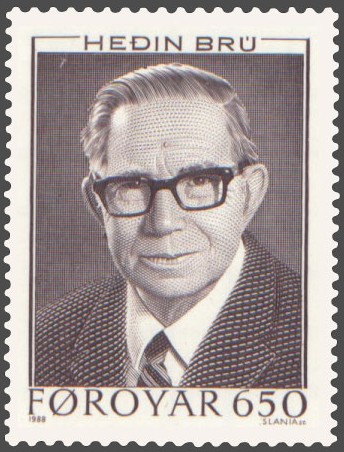

Brú, Heðin.

Brú, Heðin.