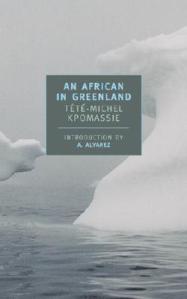

An African in Greenland by Tété-Michel Kpomassie (trans. by James Kirkup, 1983; intro. A. Alvarez). New York Review Books, 2001.

An African in Greenland by Tété-Michel Kpomassie (trans. by James Kirkup, 1983; intro. A. Alvarez). New York Review Books, 2001.

Tété-Michel Kpomassie is an extraordinary person and an extraordinary writer. His decision to leave his native Togo in 1959 and travel alone to Greenland puts him among some of the most determined Arctic travelers of the last few centuries. His choice of destination is surprising, until one reads his account of it. This book, his absorbing travel memoir, won the Prix Littéraire Francophone in 1981.

His first chapter, “The Snake in the Coconut Tree,” reads like the excellent start of an absorbing novel about African life. His uncle wanted to wake the young man to join a party of his brothers going to the nearby coconut plantation to harvest coconuts. Tété-Michel did not want to wake up and did not want to go to collect coconuts–he had a premonition that something very bad would happen that day if he went. But, on the impatient uncle’s orders, his brother filled a coconut-gourd bowl with water and dumped it on him; at last, soaked and resigned, Tété-Michel got up and joined the expedition. With practiced skill, he shinnied high up into the first coconut tree, without a rope, to dislodge the bunches of coconuts at the very top. But he also dislodged a nest of snakes. He had no weapon and few choices, when faced with the venomous reptile. He tried to avoid the snake and climb down ahead of it, but it slithered over his head and down his back–the last ten feet, he fell to the ground. It is unclear whether he was bitten or not, but, whether from venom, from venom antidote poisons, from injury, or plain shock, he soon lapsed into fever and delirium. In the next chapter, “The Sacred Forest,” he was taken deep into the territory of the python cult and its priestess. She discerned reasons she believed accounted for his condition, including seeing a dead snake in the past, and performed healing rituals. In return for this service–Tété-Michel did survive–she expected his father to dedicate him to the python cult, as an apprentice for its priesthood. The young man was horrified at this prospect. An alternative came from an unlikely place!

While he was still convalescing, the young man got books from the missionary bookshop in their town of Lomé. Among these was a book about Greenland, The Eskimos from Greenland to Alaska by Dr. Robert Gessain. He studied its photographs and learned that Greenland lay mostly north of the Arctic Circle and was incredibly cold (not sweltering as it is in Togo), but above all, it had no snakes! He adopted a fixed purpose–to leave his home and travel by himself to Greenland, going as far north as he could, and settling there. It was 1957 when he resolved to do this and made plans to run away. He would go to Abidjan in the Ivory Coast and visit an aunt who lived there; from that point, instead of returning home, he would work his way up the West African coast, obtain passage to Europe, and finally, sail to Greenland from Denmark. At that time, Greenland was a county of Denmark, its former colonial ruler. (Greenland would gain limited home rule in 1979 and full self-rule in 2009.)

Several stops, and some backtracking to Togo, were required before he finally booked passage for Europe on a ship leaving from Dakar, Senegal. For 6 months, he had worked as a translator at the Togolese embassy in Dakar, earning enough money to begin his trip. Throughout his travels, he was tremendously resourceful at finding kind people who would take him in to live and help him in various crucial ways, often finding him jobs. Besides working at those various jobs, he took correspondence courses in the languages he would need to master along the way. His graded papers often did not catch up with him before he had to move again, so he decided to teach himself with the French classics–from the 16th century onward! “My large suitcase eventually contained more books than clothes,” he writes. His writing talent must have emerged early, as he kept extensive journals on his trip, which took quite a few years and much patience. A French friend that he made encouraged this writing, suggesting that his perspective, derived from a traditional African culture, would shed new light on Eskimo customs and make his comparative observations uniquely interesting.

His boat to Marseille, France left in May of 1963. Summing up his travels so far, he remarks ironically: “And that is how, in this era of interplanetary flight, it took me six years to get out of West Africa.” He was able to enter France at the port of Marseille with just his identity card because Togo had been a former French colony. He took the seven-hour train trip to Paris. With a letter of introduction in hand, he simply presented himself at the home of a French government minister and explained his life’s mission “to link Greenland with Africa.” Remarkably, the government official received him sympathetically and gave him lodgings there for three months and, after that, a lifetime of support and advice, acting as a second father to him. This kind of story is repeated again and again in An African in Greenland: events testify to Kpomassie’s undoubted personal charisma, sincerity, and dedication to his goal. He pushed on to Bonn, Germany where he worked for two years and continued his self-education. He describes a potential advantage that his unorthodox path had over traditional education: “As for university studies, it seemed to me that without them I had remained more African: an African graduate would have spurned the risks I took and found a niche in some government ministry.”

At last, he reached Copenhagen, picking up Danish during a three-month delay while he waited for a visa to enter Greenland (his French ministry friend helped him get the authorization). In all, it had taken 8 years since he first left Togo to get this far.

The book turns now in Part II to a new chapter in his life, “The Call of the Cold.” As he intended, the sea voyage allowed his body to adapt to dropping temperatures gradually. On June 23, he saw his first ice floes: “Some were white, others green or blue. A brilliant sun, cold as steel, glittered on them and transformed the sea into a fairy-tale world: a vast ice-blue expanse strewn with great chunks of crystal” (p. 79). Four days later, they landed at Julianehåb, or K’akortoq, “the White One.” With a natural sense of the dramatic, he prepared to disembark and make his entrance for the Inuit people gathered at the dock, who had not seen a black man before in person.

As soon as they saw me, all talking stopped. So intense was the silence, you could have heard a gnat in flight. Then they started to smile again, the women with slightly lowered eyes. When I was standing before them on the wharf, they all raised their heads to look me full in the face. Some children clung to their mothers’ coats, and others began to scream with fright or to weep. Others spoke the names of Toornaarsuk and Qvivittoq, spirits who live in the mountains…. That’s what I was for those children, and not an Inuk [singular of Inuit] like themselves. …

The scene made me think of the Lilliputians surrounding Gulliver. I had started on a voyage of discovery, only to find that it was I who was being discovered. (pp. 82-83)

But Tété-Michel Kpomassie was quite welcome among the adults who vied to give him a place to stay, their customary hospitality salted with a keen curiosity about him. From then on, he was simply called Mikili (nickname for Michel or Michael) by those he met in Greenland. He made friends readily in all but a few exceptional cases during his time there. As with most travelers to a very different place, the most difficult adjustment was the unfamiliar food. Food preferences and aversions are learned in childhood and adults are less adaptable, but necessity teaches even adults. His first host family prepared a large plate of raw whale skin and seal blubber! He did his best with it; in his book he confesses that his revulsion at first was so great that he considered getting back on the Danish ship still at port. He asked himself, “Could I suddenly give up what had taken me so long to achieve, just because of a bit of raw whale skin?” No, he decided, and the process of learning and adapting to the local lifestyle began in earnest.

Mikili arrived in summer, when the midnight sun kept people restless and active all night. In the days he was taken on endless rounds of coffee visiting, and at night to dances among the young people, who did plenty of drinking. On another day he chose to visit the residents at a home for the elderly. This scene in particular was very touching to me because of his deep interest and respect for all the people he met there. After a few weeks in this southern coastal town though, he lamented the continual dancing and drinking parties that occupied the young people, along with their casual sexual pairings, as it seemed to him. He is honest too about his own behavior at that time, admitting that he indulged in some sexual relationships with girls there; however, he was troubled and frankly perplexed by the rapid swapping of partners, and felt the sting of jealousy. He wished to move farther north to “the Greenland of my dreams. I wanted to live with the seal hunters, ride in a sledge, sleep in an igloo” (p. 112). Anyone reading his memoir up to this point will have no doubt that if he can find the means, he has more than enough determination to do all these things.

As it turned out, he did all these things and more. For example, he went ice fishing and also learned the backbreaking routines of the boating fishermen, helping them haul in their nets during the long Arctic nights. As he traveled north, he was also moving into the long dark winter. He stopped at several towns along Greenland’s western coast, and saw the aurora borealis–the northern lights–for the first time:

…a great deep-folded phosphorescent curtain, which moved and shimmered, turning rapidly from white to yellow, from pink to red. The curtain suddenly rose, then fell again further on. The wind shook it gently like an immense transparent drapery carried by the breeze and drifting on thin air. Its movements were now regular as an ocean swell, now hurried, jerky, leaping and tumbling like a kite…. I stood watching it for ten minutes, stunned and fascinated. (p. 145)

By the time he reached Jakobshavn, its port was beginning to freeze and he realized he would have to winter over in this town before he could ship out again to his dreamed-of destination of Thule in the far north. In the end, he made it only as far north as Upernavik, but his life there, staying with the family of Robert Mattaaq in their small cottage, provided some of the most moving and thoughtful passages in this book, which displays those qualities abundantly throughout.

I most admired his willingness to share very Spartan accommodations with his hosts. While he noticed the hardships of poverty, the lack of sanitation or comforts, he never judged people by their physical situation but by their character. In one instance, he willingly chose the home of a poor, even outcast family over the grudging offer from a richer resident who had snubbed him earlier (and remained rather mean-spirited). He observed his fellow human beings with clarity and honesty, but always with compassion and respect. Reading his reminiscences made me wish to emulate his outlook in the face of difficult circumstances.

You may wonder now if he settled there for life, taking Greenland as his new home. I should say that it became a second home for him, one he returned to gladly throughout his life. Let me give you his own poignant words about why he decided to go back to Africa, to see his family again, of course, but more than that, to respond to a new aspect of his calling:

I had adapted so well to Greenland that I believed nothing could stop me spending the rest of my days there. Apart from a sled and a dog team, I needed only a fishing boat and a roof of my own to live happily in the Arctic. … But if I were to live out my life in the Arctic, what use would it be to my fellow countrymen, to my native land? Having tried and succeeded in this polar venture, was it not my duty to return to my brothers in Africa and become the “storyteller” of this glacial land of midnight sun and endless night? After the degradation of colonization and the struggle for independence, wasn’t it the task of educators to open their continent to fresh horizons? Should I not play my small part in that task and help the youth of Africa open their minds to the outside world? (p. 293)

And that is exactly what he did. He wrote this amazing memoir, which was published in France in 1977. As I mentioned earlier, it won the Prix Littéraire Francophone International in 1981. The English translation I read was done in 1983. Kpomassie lives in France, but travels and speaks widely. I loved finding this recent picture of him, speaking to the Bergen (Norway) Student Society in 2011.

And that is exactly what he did. He wrote this amazing memoir, which was published in France in 1977. As I mentioned earlier, it won the Prix Littéraire Francophone International in 1981. The English translation I read was done in 1983. Kpomassie lives in France, but travels and speaks widely. I loved finding this recent picture of him, speaking to the Bergen (Norway) Student Society in 2011.

I wish to thank Aarti Chapati for recommending this book in the Diversiverse reading event organized by her. Her review of the book inspired me and I made it one of my reading goals for the event–it has taken me a while to finish and write about it. Do read her excellent review of the book at her blog Booklust. And I wouldn’t have found Diversiverse if it hadn’t been for Becca of I’m Lost in Books and Tanya of Mom’s Small Victories, who hosted their Travel the World in Books readathon with such warmth, energy, and insight. This book is also part of my participation in Nonfiction November!

Related link:

Related post:

What an amazing journey and book. Thanks for sharing your review, it’s not one I would normally come across but I am intrigued by it. Great job on your Travel the World in Books reading journey!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Travel the World in Books 2015: Bookmark Mini-Challenge and Some Books of the Americas #TTWIBRAT | The Fictional 100

Pingback: #TTWIB MARCH 2016 READALONG–An African in Greenland by Tété-Michel Kpomassie | The Fictional 100

Pingback: Travel the World in Books is Reading “An African in Greenland” | Northern Lights Reading Project

Pingback: Faroe Islands: “The Old Man and His Sons” by Heðin Brú #TTWIB | Northern Lights Reading Project

Pingback: The Ultimate Winter Reading List: Get Cozy and Travel the World in Books